Labs and Lytes 040

Author: Dr Nasreen Bahemia

Peer reviewers: Dr Craig Johnston, A/Prof Chris Nickson

A 56-year-old female presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with 2 days of severe nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. She was also getting progressively drowsier while waiting in ED. Her last meal, a large quantity of homemade pasta with mushroom that she foraged, was 2 days prior to presentation. She had a past medical history of hypertension and was a social drinker.

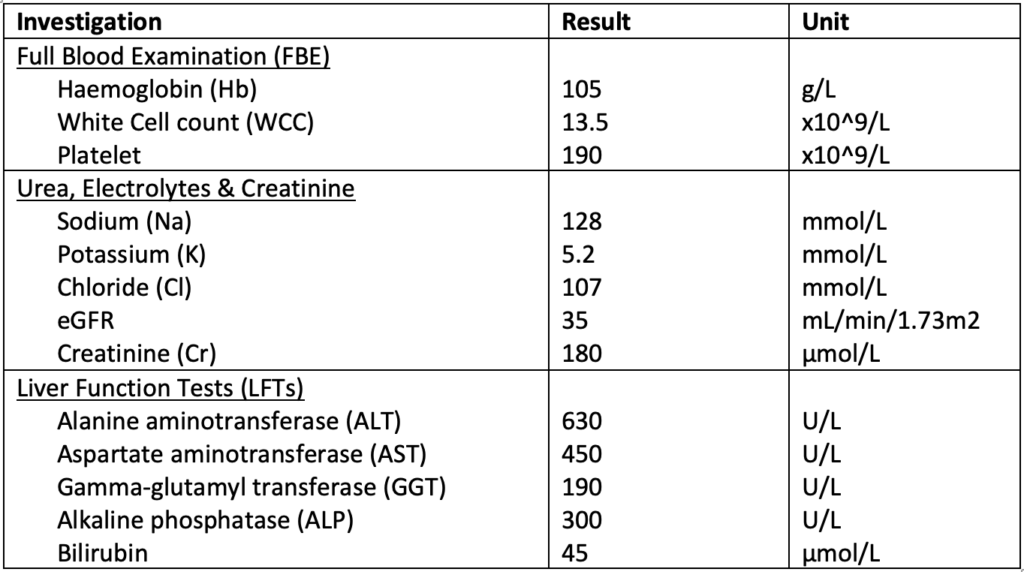

Results of her laboratory investigations include:

Q1. Interpret the Liver Function Tests (LFTs).

The blood tests show profoundly deranged LFTs. This is a mixed picture of LFT derangement, with transaminitis being more pronounced. The AST:ALT ratio <1. This is specific for hepatocellular damage, with differentials including ischaemic hepatitis, hepato-toxins or viral hepatitis.

Fulminant hepatitis (Hôpital Beaujon classification1), or hyperacute hepatitis (Kings College criteria2), depending on the classification used, is diagnosed based on the time from jaundice to encephalopathy. In this case, the timeline of symptoms onset (from asymptomatic to encephalopathy within 2 days) made this a case of fulminant hepatitis.

Coagulation studies also need to be done to assess the synthetic function of the liver. A ‘liver screen’ should also be considered. This typically includes:

- Viral hepatitis screen (Hepatitis A/B/C serology, Epstein Barr Virus (EBV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

- Autoimmune screen (Anti-Mitochondrial Antibodies (AMA), Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA), Anti-Smooth Muscle Antibodies (ASMA), p-Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies (p-ANCA), IgM/IgG)

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin

- Screen for infiltrative diseases (copper level, ceruloplasmin, ferritin)

- Blood paracetamol level

Glucose and ammonia levels would also be useful to confirm complications of acute liver failure.

Other investigations to consider include imaging of the liver with ultrasound and computerised tomography (CT) to assess for any changes to the liver parenchyma or vasculature, such as portal vein thrombosis or Budd Chiari Syndrome (hepatic venous outflow obstruction).

Q2. What was causing the abnormality in this case?

In this case, the history pointed towards mushroom poisoning. Most cases of mushroom poisoning are self-limiting episodes of gastrointestinal upset. Whilst very rare, severe mushroom toxicity can occur and can even be fatal.

There are many different syndromes associated with mushroom poisoning in Australia including cholinergic, hallucinogenic, glutaminergic, disulfram-like and hepatotoxic3. The hepatotoxic mushrooms result from 3 different types of cyclopeptide (amatoxin, phallotoxin and virotoxin). Symptoms usually start between 6 and 24 hours after ingestion of the mushrooms containing these peptides (delayed, rather than early, onset).

Amanita phalloides, more commonly known as the death cap mushroom, is the most commonly eaten poisonous mushroom in Victoria. It usually grows under oak trees and its distinguishing features include a smooth, yellowish-green to brown cap, white gills, white stem, membranous skirt on stem and cup-like structure around the base of the stem4. It contains amatoxin, which irreversibly binds to RNA polymerase II, thus inhibiting DNA transcription, resulting in arrest of protein synthesis and eventually cell necrosis5. Patients with suspected Amanita phalloides poisoning should be managed in consultation with a clinical toxicology service and should be referred to a liver transplant centre if they fail to improve.

Other causes of fulminant liver failure are

- Viruses (for example, Hepatitis A, B, C, EBV, CMV)

- Autoimmune

- Alcoholic

- Toxins

- Others- Acute fatty liver of pregnancy, Haemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes and Low Platelets (HELLP) Syndrome, Budd Chiari, ischaemic hepatitis, infiltrative diseases e.g., Wilson’s disease

Q3. What are the West Haven criteria?

West Haven criteria6 classify the severity of hepatic encephalopathy:

- Grade I- Changes in behaviour with minimal change in level of consciousness

- Grade II- Gross disorientation, drowsiness, asterixis present, inappropriate behavior

- Grade III- Marked confusion, incoherent speech, somnolence but arousable to vocal stimuli

- Grade IV- Comatose, unresponsive to pain

Q4. How should the patient be managed?

This patient is highly likely to have amatoxin-mediated hepatoxicity from Amanita phalloides mushroom poisoning. Management priorities3,7,8 are as follows:

Resuscitation to address immediate life threats (if present):

- Airway – patients are often obtunded and require intubation for airway protection

- Breathing- Hyperventilate to aim for a low-normal PaCO2 for neuroprotection

- Circulation- Patients should receive IV fluid resuscitation, particularly if significant diarrhoea/vomiting causing hypovolaemic shock. Vasopressors such as noradrenaline are often required (systemic vasodilation is common in hepatic failure).

- Disability- treat hypoglycaemia if present.

Supportive care and monitoring

- Prioritise short-acting agents, avoid medications that accumulate in hepatic failure

- Usually ICU measures (e.g. FASTHUGS)

- 4H therapy for hepatic failure

Investigations (as discussed previously)

Decontamination and Enhanced Elimination

- Multidose activated charcoal be beneficial in an alert and compliant patient to enhance elimination as amatoxin undergoes enterohepatic circulation. The timeframe for administration of charcoal post Amanita phalloides poisoning may be up to 48 hours9. This should be discussed with a toxicologist.

Antidotes and specific therapies

- Silibinin an antidote used in cases of Amanita phalloides poisoning10. It is a milk-thistle extract and works by competing with amatoxins for transmembrane transport, thus inhibits amatoxin uptake by hepatocytes. The recommended dose is 5mg/kg by IV infusion over 1 hour, then 20mg/kg/day for up to 3 days.

- If silibilin is unavailable, alternatives such as rifampicin (600 mg IV daily) or benzylpenicillin (600mg/kg/day in divided doses for first day) may be used9.

- N- Acetylcysteine is also used, with the same infusion protocol as for paracetamol toxicity9.

Disposition

- Admission to ICU and early discussion with a hepatologist to identify patients who are likely to require (and are candidates for) a liver transplant.

Q5. What is Quadruple-H therapy?

A key cause of mortality in acute liver failure is cerebral oedema. The exact pathophysiology is complex, but an important factor is the accumulation of metabolic toxins such as ammonia.

Quadruple-H therapy is a combined neuroprotective approach to manage cerebral oedema11. It refers to hypernatraemia, hyperventilation, haemodialysis, and induced hypothermia. It should be instituted in all patients with high grade encephalopathy requiring intubation.

Hyperventilation

Patients with liver failure often have a high respiratory rate at baseline. Aiming for a PaCO2 at lower limit of normal, i.e., 35mmHg, in a ventilated patient reduces cerebral hyperaemia. Aggressive hyperventilation should be avoided as it leads to severe vasoconstriction which can lead to cerebral ischaemia.

Hypernatraemia

Osmotherapy, with hypertonic saline (23.4% sodium chloride at 1-10ml/hr through a dedicated Central Venous Catheter (CVC) lumen), reduce cerebral oedema and intracranial pressure by causing the efflux of water from brain tissue into the bloodstream. Aim Na 148-152 mmol/L.

Haemofiltration

Haemofiltration has a role not only in supporting the kidneys, but also as a neuroprotective strategy. It clears ammonia, allows fluid removal, and facilitates management of electrolyte. A higher than usual dialysis dose of 40-60ml/kg/hr should be prescribed.

Hypothermia

Aiming for a lower core temp (35 oC) reduces cerebral metabolic rate and cerebral blood flow. This can be achieved by using cooling blankets or adjusting the CRRT circuit.

Q6. The patient remained in ICU for seven days since initial presentation, with minimal improvement on quadruple H. What was the next appropriate step?

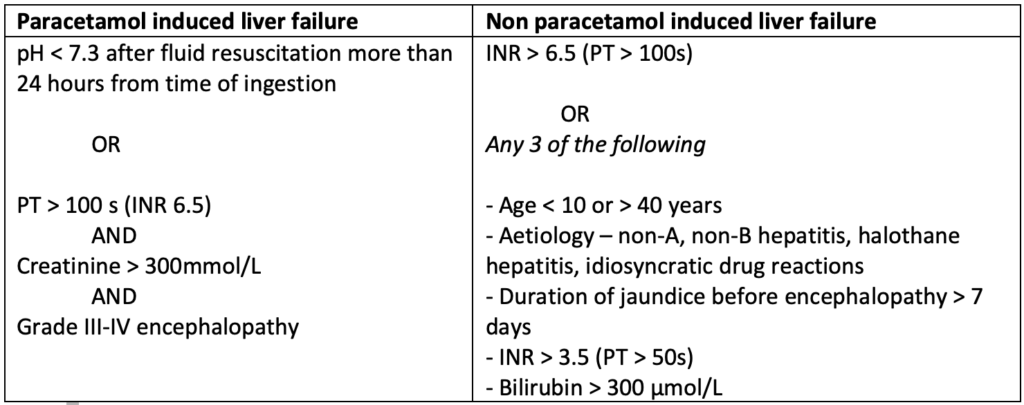

The King’s College Criteria2 can be used to risk stratify patients and identify those who will require a liver transplantation. If the patient’s trajectory is concerning, early referral to a liver transplant centre is crucial, even before she meets King’s College criteria.

Alternatively, the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score12 can be used. It predicts 90-day mortality and is calculated based on serum Na, creatinine, bilirubin, and INR, and whether the patient has received dialysis in the past week. The higher the MELD score, the higher the predicted mortality.

References

- Bernuau, J., Rueff, B., & Benhamou, J. P. (1986, May). Fulminant and subfulminant liver failure: definitions and causes. Semin Liver Dis, 6(2), 97-106. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1040593

- O’Grady, J. G., Alexander, G. J., Hayllar, K. M., & Williams, R. (1989, Aug). Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure. Gastroenterology, 97(2), 439-445. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(89)90081-4

- Nickson, C. (2020). Mushroom toxicity. LITFL.com. Available from URL: https://litfl.com/mushroom-toxicity/ [Accessed 10 February 2023]

- Death Cap – Amanita phalloides. (2022). Royal Botanical Gardens Victoria. https://www.rbg.vic.gov.au/science/herbarium/death-cap/

- Berger, K. J., & Guss, D. A. (2005, 2005/01/01/). Mycotoxins revisited: Part I. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 28(1), 53-62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.08.013

- Ferenci, P., Lockwood, A., Mullen, K., Tarter, R., Weissenborn, K., & Blei, A. T. (2002, Mar). Hepatic encephalopathy–definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998. Hepatology, 35(3), 716-721. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2002.31250

- Nickson, C. (2020a). Fulminant Hepatic Failure. https://litfl.com/fulminant-hepatic-failure/ [Accessed 10 February 2023]

- Yartsev, A. (2015). Management of acute liver failure. https://derangedphysiology.com/required-reading/gastroenterology-and-hepatology/Chapter%201.1.3/management-acute-liver-failure [Accessed 10February 2023]

- Austin Clinical Toxicology Service. (2020). Amanita phalloides (Death Cap) and other Cyclopeptide Mushrooms https://www.austin.org.au/Assets/Files/Amanita%20Guideline_SG%20Final.pdf

- Austin Health Clinical Toxicology Service. (2021). Silibinin https://www.austin.org.au/Assets/Files/Silibinin_2021_Final.pdf

- Warrillow, S. J.; Bellomo, R. (2014, Jan). Preventing cerebral oedema in acute liver failure: the case for quadruple-H therapy. Anaesth Intensive Care, 42(1), 78-88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0310057×1404200114

- Kamath, P. S., & Kim, W. R. (2007, Mar). The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD). Hepatology, 45(3), 797-805. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.21563

All case-based scenarios on INTENSIVE are fictional. They may include realistic non-identifiable clinical data and are derived from learning points taken from clinical practice. Clinical details are not those of any particular person; they are created to add educational value to the scenarios.