Author: Dr Kerrianne Huynh

Peer reviewer: A/Prof Chris Nickson

Everything ECMO 037

On desedation, a patient being treated with VV ECMO for severe COVID pneumonia is not waking up appropriately and has upper motor neuron signs. CT brain shows:

Q1. What does the image show?

The image is from Radiopaedia.org, Basal Ganglia bleed case, where Assoc Prof Frank Gaillard reports the findings as:

Axial non contrast CT image demonstrates a hyperdense focus centered on the globus pallidus on the left with a faint rim of low attenuation. Findings are characteristic of a basal ganglia hemorrhage.

Follow the link to learn more about radiological imaging of Intracranial Haemorrhage (ICH) on Radiopaedia.org.

Q2. What is the incidence of intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) in ECMO patients?

Intracranial haemorrhage is a common complication in adults treated with ECMO, with a reported an incidence of 1.8-21% [1-3]. According to the ELSO Guidelines 2021, intracranial haemorrhage encapsulates intraparenchymal, subdual and subarachnoid haemorrhage [4].

There is mixed evidence regarding the association between ICH and the mode of ECMO. An examination of the ELSO registry suggested that ICH is more common in VV ECMO than VA ECMO [5]. However, a systematic review did not find that VA ECMO increased the risk of ICH nor an increased mortality, suggesting the need for further research [2].

Q3. What are the risk factors for ICH in ECMO patients?

Different studies identify multiple risk factors, including:

- ECMO factors

- Longer duration of ECMO [6, 7]

- Rapid hypocapnia at ECMO initiation[2, 8]

- PaO2 increase at ECMO initiation [8]

- Patient factors

- Female gender [9]

- High pre-cannulation SOFA score [1]

- Septic shock[1, 10]

- Pre ECMO morbidity [2]

- Haematological factors

- Platelet transfusion volume [1, 2, 6]

- Red cell transfusion volume [1, 2]

- Thrombocytopaenia <25-30 x 109/ml [1, 9, 10]

- Preadmission anti thrombotic therapy [1, 11]

- Use of heparin [2, 9]

- Spontaneous extracranial haemorrhage[1]

- Increased activated clotting time (ACT) [6]

- Haemolysis [10]

- Renal factors

- Dialysis [1, 9, 10]

- Creatinine >230 umol/L [9]

- Renal failure on ICU admission[2, 8, 10]

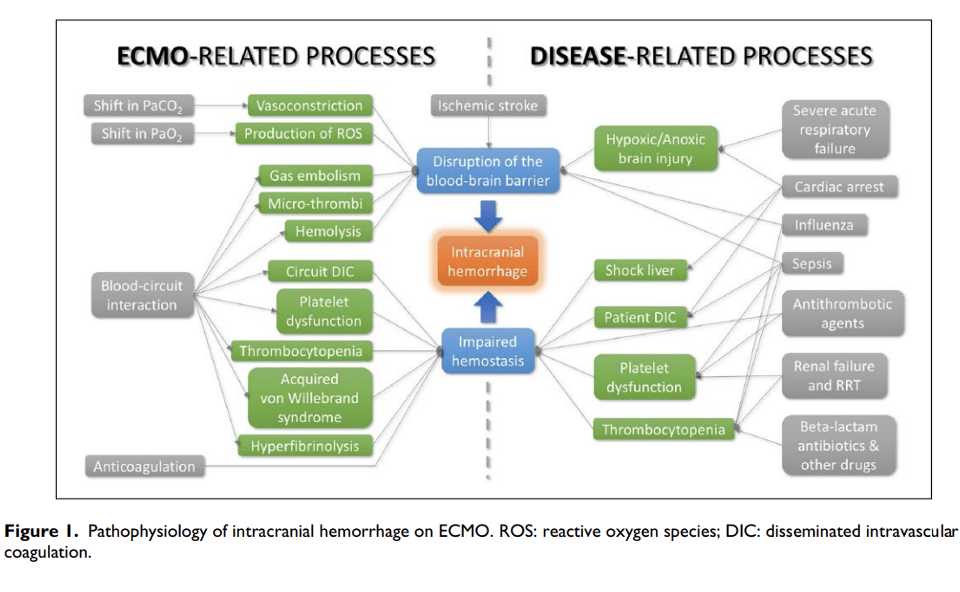

Q4. What are the mechanisms of ICH in ECMO patients?

There are multiple mechanisms of ICH. These include:

- Pre ECMO factors [2]

- Low cerebral blood flow

- Hypoxia

- Acidosis

- Haemostatic disorders due to liver failure

- Reperfusion injury at ECMO initiation

- Rapid shifts in PaCO2 and PaO2 lead to vasoconstriction

- Prothrombotic conditions such as sepsis

- Pre-existing anticoagulation and antiplatelets

- Impaired haemostasis[1, 2, 6]

- Systemic effects of cardiopulmonary bypass, including platelet dysfunction and consumption

- Concurrent anticoagulation and antiplatelets

- Haemodilution: factor XIII, von Willebrand factor, fibrinogen, factor X

- Production of thrombin

- Haemolysis may contribute by the release of free haemoglobin, which can lead to disruption of the blood brain barrier, oxidative stress, and depletion of nitric oxide

- Disruption of the blood brain barrier

- This leads to plasma and erythrocyte extravasation

- This is followed by impaired haemostasis due to above factors, the formation of microthrombi, infarctions and subsequent haemorrhagic transformation [10]

How these mechanisms interact is illustrated in this diagram from Cavayas et al [10]:

Q5. How do you diagnose ICH in ECMO patients?

There is currently no standardised screening process for ICH in ECMO patients at the Alfred.

Daily neurological examination is an important screening tool [5], but is confounded by the heavy sedation and/or neuromuscular blockade that many patients receive. Clinical manifestations may include focal sensorimotor deficits, seizures, pupillary abnormalities, coma, or brain death. These findings may only be recognised when the effects of sedation and/or paralysis have resolved.

Previous studies have taken an approach of routine cranial scanning whenever the patient was being scanned for a different indication, in addition to scanning in response to neurological deterioration [11, 12]. These studies tend to show a higher proportion of ICH, which suggests that ICH is under-recognised.

Q6. What is the prognosis for ICH in ECMO patients?

Notably, the major cause of death in ECMO patients is not irreversible pulmonary or cardiac failure; it is cerebral injury [12-14]. Intracranial bleeding is the most devastating bleeding complication that occurs, as it is associated with a higher morbidity and mortality [8, 10]. During the H1N1 pandemic in Australia and New Zealand, ICH was the most common cause of death among patients treated with ECMO [14]. In the ELSO registry, only 11% of patients on VA ECMO and 26% of those on VV ECMO who developed ICH survived to hospital discharge [5, 15]. A systematic review described mortality between 32-100% for ICH [2]. Patients that do survive are more likely to have longer hospital stays and, if they survive the hospital stay, are more likely to be discharged to a long term facility [16].

One study described the relationship between mortality and the characteristics of the ICH, including presence of intraparenchymal haematoma, volume of the haemorrhage, presence of IVH, SAH Fischer grade, hydrocephalus, midline shift and absent basal cisterns. The findings are similar to those of non-ECMO patients [9].

Q7. What is the management of ICH in ECMO patients?

Management of ICH in ECMO involves careful deliberation with senior clinicians.

An important consideration after the diagnosis of ICH is to determine the overall prognosis of the patient and the need for ECMO support. A re-evaluation of the goals of care may be necessary. In one study of 65 ECMO patients on ECMO with ICH, 42% of patients had ECMO treatment withdrawn, with an expected subsequent 30-day mortality of 100% [11]. Ideally, the patient should be decannulated if safe to do so, thereby removing the need for anticoagulation. However, few patients may fall into this category.

Conservative neuroprotective measures to minimise secondary injury include maintenance of euglycaemia, normothermia and normocapnia. Hypertension should be treated. If there are signs of raised ICP, hyperosmolar therapy can be administered.

The management of anticoagulation balances extension of the bleed against circuit thrombosis. Such interventions include reduction or cessation of heparin (or other anticoagulation used during ECMO therapy), administration of antiplatelets and anti-fibrinolytics. Aiming for less aggressive anticoagulation still risks extension of the ICH[6]. Anticoagulation can be withheld for prolonged periods in patients on VV ECMO, with good long-term outcomes [17].

Neurosurgical intervention may be considered in certain situations, for instance as a life-saving measure in a patient who, if not for the ICH, would be expected to have a good outcome. Neurosurgical treatment is associated with severe morbidity but has been successful in selected cases [2]. If the patient can be weaned from ECMO, this greatly facilitates the management of ICH [10]. If the patient cannot be weaned from ECMO, heparin needs to be ceased and reversed to decrease progression of the ICH, as well as intra operative and postoperative bleeding. The recommencement of anticoagulation in the postoperative period is a complex question that requires a multidisciplinary approach.

Regarding the outcome of these patients post neurosurgical intervention, one study of 65 patients described a 30-day mortality of 58% for the 40% of patients who proceeded to neurosurgery, with 81% of deaths attributable to the ICH[11]. Another study described nine ECMO patients with ICH that underwent neurosurgical intervention, resulting in two survivors [2]. These studies highlight that outcomes are often poor despite invasive neurosurgical intervention.

References

- Fletcher-Sandersjöö A, Bartek J Jr, Thelin EP, et al. Predictors of intracranial hemorrhage in adult patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: an observational cohort study [published correction appears in J Intensive Care. 2020 Jan 3;8:2]. J Intensive Care. 2017;5:27. Published 2017 May 22. doi:10.1186/s40560-017-0223-2 [article]

- Fletcher-Sandersjöö A, Thelin EP, Bartek J Jr, et al. Incidence, Outcome, and Predictors of Intracranial Hemorrhage in Adult Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Systematic and Narrative Review. Front Neurol. 2018;9:548. Published 2018 Jul 6. doi:10.3389/fneur.2018.00548. [article]

- Gattinoni L, Carlesso E, Langer T. Clinical review: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):243. doi:10.1186/cc10490 [article]

- E. L. S. O. (ELSO), “Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO), ELSO Registry Data Definitions, 01-07-2021. [webpage]

- Lorusso R, Barili F, Mauro MD, et al. In-Hospital Neurologic Complications in Adult Patients Undergoing Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: Results From the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(10):e964-e972. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000001865

- Omar HR, Mirsaeidi M, Mangar D, Camporesi EM. Duration of ECMO Is an Independent Predictor of Intracranial Hemorrhage Occurring During ECMO Support. ASAIO J. 2016;62(5):634-636. doi:10.1097/MAT.0000000000000368C.

- Aubron C, DePuydt J, Belon F, et al. Predictive factors of bleeding events in adults undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6(1):97. doi:10.1186/s13613-016-0196-7 [article]

- Luyt CE, Bréchot N, Demondion P, et al. Brain injury during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(5):897-907. doi:10.1007/s00134-016-4318-3

- Kasirajan V, Smedira NG, McCarthy JF, Casselman F, Boparai N, McCarthy PM. Risk factors for intracranial hemorrhage in adults on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15(4):508-514. doi:10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00061-5

- Cavayas YA, Del Sorbo L, Fan E. Intracranial hemorrhage in adults on ECMO. Perfusion. 2018;33(1_suppl):42-50. doi:10.1177/0267659118766435

- Fletcher-Sandersjöö A, Thelin EP, Bartek J Jr, Elmi-Terander A, Broman M, Bellander BM. Management of intracranial hemorrhage in adult patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): An observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0190365. Published 2017 Dec 21. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0190365 [article]

- Risnes I, Wagner K, Nome T, et al. Cerebral outcome in adult patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(4):1401-1406. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.10.008

- Mateen FJ, Muralidharan R, Shinohara RT, Parisi JE, Schears GJ, Wijdicks EF. Neurological injury in adults treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(12):1543-1549. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.209 [article]

- Australia and New Zealand Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ANZ ECMO) Influenza Investigators, Davies A, Jones D, et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for 2009 Influenza A(H1N1) Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. JAMA. 2009;302(17):1888-1895. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1535 [article]

- Lorusso R, Gelsomino S, Parise O, et al. Neurologic Injury in Adults Supported With Veno-Venous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Respiratory Failure: Findings From the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Database. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(8):1389-1397. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002502

- Nasr DM, Rabinstein AA. Neurologic Complications of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. J Clin Neurol. 2015;11(4):383-389. doi:10.3988/jcn.2015.11.4.383 [article]

- Lockie CJA, Gillon SA, Barrett NA, et al. Severe Respiratory Failure, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, and Intracranial Hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(10):1642-1649. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002579